Paradise Lost & Found

Essay by Lisa McCarty for the exhibition catalog for Paradise Road & Paradise Out-Front at The Southern, Charleston, SC | Return to Selected Writings

Featuring works by Eliot Dudik, Ben Alper, Ian van Coller, Mark Dorf, Matt Eich, Frances Jakubek, Thalassa Raasch, Jared Ragland, Justin James Reed, Anastasia Samoylova, Bryan Schutmaat , Aline Smithson, Katherine Squier, and Susan Worsham.

The idea of paradise has persisted for as long as stories have been told, yet there has never been consensus on what it is, where it is, and if it can be reached. There may in fact only be two commonly shared beliefs concerning paradise, the first being that there are infinite definitions of it. However, if paradise is in the eye of the beholder, then how do we begin to contemplate what it can be to one and all in the present moment? A starting point may be the origin story of this weighty word.

Many Christians believe that humanity was expelled from paradise, but that the soul may be able to return to it in the afterlife. This ideology, which often conflates Heaven and the Garden of Eden, was not the first definition of paradise though. As Alessandro Scafi outlines in his book, Maps of Paradise, in the late second century B.C., “a term pointing to ‘paradise’ first emerged on the lips of the Medes, a powerful and, for us, enigmatic ancient tribe in the Middle East and central Asia.” Scafi goes on to say that, “a Median word, possibly ‘pari-daiza’, passed to the Persians to signify an enclosure. From pari-, meaning ‘around’, and daiza-, meaning ‘a wall made of a malleable substance’, such as clay, in ancient Iran the word stood for something surrounded by a wall.”1 Ultimately a version of ‘pari-daiza’ comes to be used in Persian to describe, “a hunting park for the enjoyment of the elite, especially kings.”2 What an incongruous beginning for what has become such an idealistic concept. Still, maybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that historically, paradise has been considered either exclusive or unattainable in one’s lifetime.

Fast forward a few millennia and versions of this original definition of paradise continue to thrive in both words and pictures. By 1321 the Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s completes his three-part Divine Comedy in which readers travel with Dante through the Inferno and Purgatorio to reach Paradiso. By 1667, the English poet John Milton pens an account of the Biblical story of the Fall of Man in Paradise Lost followed by the story of the temptation of Christ in Paradise Regained. During this same period, Western cartographers also attempt to identify the location of the Garden of Eden in elaborate maps, attempting to regain paradise as Milton did. Such maps, now considered examples of “persuasive cartography,”3 persist as late as 1855 with seductive names such as Paradise According to Three Different Hypotheses, The Ordering of Paradise, The Opportunity of Paradise, and Situation of the Terrestrial Paradise. Through these persuasive maps, classic works of literature, religious histories, and linguistic roots, a dominant conception of paradise does persist. However, there are still numerous graphic alternatives to explore. In fact, if you’re an artist, you may believe that paradise can be seen in the present moment.

This point leads me to the second commonly shared belief concerning paradise, namely, that paradise can be pictorially represented. This belief of course has been proliferated by a long lineage of imagemakers. Adam and Eve’s expulsion from paradise was a popular subject among Italian Renaissance painters. While many of those images withhold a full view of paradise, emphasizing loss, shame, and inaccessibility, we are still provided with a representation of it. Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch countered this trend in his infamous triptych, known as The Garden of Earthly Delights, where Eden, its ruin, and Hell are fully and vibrantly rendered. Interestingly, in this same era, paintings of earthly paradises emerge as well, usually consisting of verdant landscapes brimming with plant and animal life of all kinds. It is at this point that paradise becomes attainable, in the present moment, through the agency of artists.

Recalling the pictorial history of paradise is like reviewing a list of greatest hits from the Western canon. Depictions of a variety of paradises, Biblical and otherwise, flourish in paintings and drawings by William Blake, James Ensor, Salvador Dalí, Romare Bearden, Wassily Kandinsky, and Helen Frankenthaler, ebbing and flowing between realism and abstraction. Yet, the lineage stalls at the threshold of abstract expressionism and, seemingly, excludes photographic depictions. Such a finding raises a variety of questions: Is paradise still pictured today? And, assuming that it is, what does it look like? Can paradise be found in the world at hand? Can it be created? Can it be photographed? At least fourteen photographers consider these questions on the following pages and on the walls of The Southern Gallery of Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina in Paradise Road | Paradise Out-Front.

If we look at the land we inhabit attentively enough, can it tell us something about the past, present, and future of America? Eliot Dudik asks this question in different ways in each of his recent projects. His most recent project, Paradise Road, comes pointedly on the heels of Broken Land, in which Dudik drove a total of 30,000 miles to survey Civil War battlefield sites in 26 states. His goal for this project was not however, historic preservation. By pointing to such a divisive period and to sites where some of our country’s most horrific conflicts played out, Dudik also points to the polarized American climate of today. Ultimately he hopes such a project might “derail that seemingly inevitable tendency for repetition.”4 At first glance, the peaceful, pastoral scenes presented in Broken Land seem to be a counterpoint to the death and destruction that took place on these very sites. That is, until you realize the panoramic images are constructed with two different negatives, simultaneously united and divided.

Paradise Road is just as pointed and just as subversive. This deceptively transparent title describes the actual location of every picture in the series. There are roughly 196 Paradise Roads in the continental United States and Dudik has photographed over 90 of these Paradise Roads to date. In describing his motivation for the project Dudik told me that he wanted to “drive to paradise and see what was there,” seeing this project as a means to “take the temperature of the country.” After all, what better way to understand the state of America than by surveying its paradises?

Paradise Road is then both a literal and allegorical investigation. It lives somewhere between the traditions of American road trip projects like Robert Frank’s The Americans or Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi, and the conceptual typologies of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip might in fact be the closest relative to Paradise Road. Both projects depict and transcend exactly what is described in their titles, leaving ample room for meditation and projection. How does one begin to think about photographing the legacy of American exceptionalism in the wake of widespread economic, racial, and gender inequality? Visit enough Paradise Roads and it may all just play out before your eyes.

Two cows observe a farmer working on a broken down sedan on Paradise Road in Wittenberg, Wisconsin.

A cemetery and housing development at the edge of Zion National Park populate Paradise Road in Hurricane, Utah.

A narrow hillside divides a new high rise from a cleared field, now occupied by a pile of worn tires and a cluster of trailers on Paradise Road in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

A single mobile home with peeling mint green paint sits in a barren pasture behind a barbed wire fence on Paradise Road in Boulder, Wyoming.

The humor, the sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness and American-ness of these pictures!*

While Paradise Road lays out a lyric typology, it’s a specific one. In curating the exhibit Paradise Out-Front, Dudik zooms out to survey a constellation of paradise-related works by his peers. Despite the specificity of his own work, he provided only a spare prompt when inviting the selected artists to participate: “Send over a few jpegs that in your mind deal with the idea of paradise in some way or another. These can be literal, abstract, suggestive, counter-intuitive, whatever.” I’ve come to think of Dudik’s cryptic prompt as a sincere provocation given the aforementioned history of paradise and the current climate of present-day America. So, how do thirteen photographers working in this country in 2016 respond when asked to deal with the idea of paradise?

Aline Smithson and Ben Alper responded in opposition to traditional concepts of paradise. The title of Smithson’s works, Not as Interesting and Nothing to See, appear in the images themselves, overlaid across toned landscapes. Her lack of interest in “the rapture of Western topographies,” as she writes in her artist statement, is clear and Smithson’s candidness is refreshing. Alper is similarly uninterested, or just unable to consider an idyllic paradise given, as he states, “the state of the world, but more immediately the state of our country.” His Cocoon, Torso, and Tear (Building), are anxiety ridden but also signal transformation. What will ultimately come of that transformation is up to you.

Anastasia Samoylova, Frances Jakubek, and Mark Dorf responded to the paradise prompt skeptically providing a variety of composited images. Samoylova’s composite is sourced from a Google image search using the keyword ‘paradise.’ Her search yielded paradise as dictated by algorithm. The paradise that Google sees is a tropical one, much like conceptions of the Garden of Eden. It too is exclusionary though, as the pictures capture beach resorts and getaways that very few people ever reach. These illusive images are made tangible to create the final physical assemblage that is re-photographed. Dorf also mines the digital realm in his composited video, untitled56. In combining camera-generated and data-generated images of landscapes, he challenges viewers to questions the disparity between representations and acknowledge the limitations of representations of all kinds. Jakubek however, veers back into the realm of materiality to create her untitled works from the Carefully Omitted series. Paper ephemera from a bygone era are carefully arranged in these concrete poems, alluding to a network of interior paradises.

Bryan Schutmaat and Susan Worsham responded sincerely. Schutmaat’s image, Refuge, is surreally classical. Unabashedly referencing photographs by the likes of Ansel Adams in the twentieth century or William Henry Jackson in the nineteenth century, he clearly believes paradise can be found in this world. Worsham’s image, The Parrot Room, invokes a certain surrealism, but of the Southern variety. Only in the south could one find a sunroom inhabited by a wrought iron chair, potted plants, ripening fruit, duck decoys, a live parrot, and a marooned painting of a snow-covered Western landscape. Though most of these elements may have sat in place for years at a time, Worsham activates the space, and intervenes in it, to create her own domestic paradise.

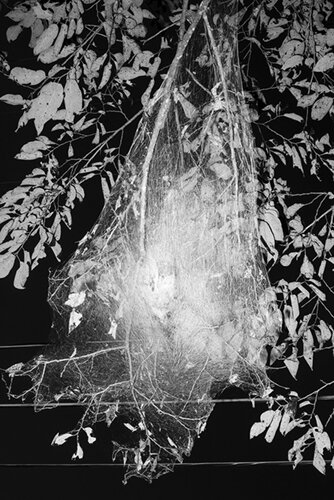

Justin James Reed and Katherine Squier provide a dose of mysticism. Reed likens paradise to psychic conditions which can only be manifested in the presence of nature. Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Every natural fact is a symbol of some spiritual fact.”4 His philosophy is played out in Reed’s associative images. I imagine the astral web of vegetation may be the vision that keeps that unnamed figure transfixed. Squier, too, attempts to elevate everyday apparitions. Here, focusing on elegantly outstretched limbs, it seems as if these obscured figures may be gatekeepers to paradise.

Ian Van Coller and Matt Eich acknowledge impermanence in their views of paradise. Van Coller’s portraits provide a closer look at what could be the next generation to inhabit Paradise Road. Though he doesn’t directly address the idea of paradise in his artist statement, his subject speaks for him. The formerly booming mining town of Butte, Montana clearly alludes to the fleeting nature of terrestrial paradise. Eich’s photographs speak to a corporal transience. In both Backyard Haircut and Side Exit we are presented with a family portrait and a tenuous façade. These images remind me that paradise isn’t always on a mountaintop or tropical island. Though inherently less permanent, home may be paradise, whether it consists of a house or not.

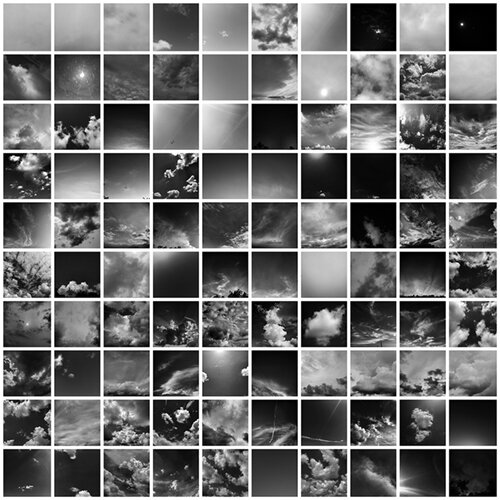

And finally, Thalassa Raasch and Jared Ragland have created their own paradises amid personal tragedy. Both have recently lost loved ones and decided to create opportunities to see paradise when they needed it most. Raasch’s images begin and end as physical monuments. Crafting handmade memorials in her own garden provides the opportunity to tangibly perform her grief and then document it. Ragland, struggling with a similar loss, looked toward the heavens instead of the earth, bringing us full circle. His series eequivalentss is a digital homage to Alfred Stieglitz’s series Equivalents and provides opportunities for prayer and meditation. By searching and photographing the sky for the duration of his mother’s battle with cancer, Ragland creates time and space to access paradise.

It appears I have, in the end, answered my own questions. Paradise is still pictured today. Paradise can be found in the world at hand. Paradise can be created and it can be photographed. There are an infinite number of paradises available to us if we look attentively.

Lisa McCarty, November 2016

NOTES

* Kerouac, Jack. Introduction. The Americans, by Robert Frank, Grove Press, 1959.

1 & 2) Scaifi, Alessandro. Maps of Paradise. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

3) Cornell University Library. The PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography, 2012, https://persuasivemaps.library.cornell.edu/. Accessed 15 November. 2016.

4) Dudik, Eliot. “Broken Land.” Lensculture, https://www.lensculture.com/projects/15204-broken-land. Accessed 20 November 2016.

5) Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Nature. James Munroe and Company, 1836.